1 前言

第三方利他行为是个体作为自身利益未被波及的旁观者, 依旧自愿支付成本惩罚违规者(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004)或者补偿受害者(Hu et al., 2015; Leliveld et al., 2012)的行为。这种行为不仅能帮助个体在复杂的社会情境中建立良好的人际互动, 而且能维护社会规范, 是非常重要的亲社会行为。与此同时, 公平规范作为最重要的社会规范之一, 有助于促进群体合作、维护良好社会秩序, 是心理学、教育学、经济学、社会学等领域都非常重视的议题。为了解人类公平维护的起源与发展, 大量研究从发展的角度考察了不同时期儿童的公平行为(如McAuliffe et al., 2017), 并发现儿童在童年早期就会避免劣势不平等(所得少于他人) (Blake et al., 2015); 到童年中期, 既会避免与自身利益相关的不公平现象(第二方惩罚) (Gummerum & Chu, 2014), 也会避免与己无关的不公平现象(第三方惩罚) (McAuliffe et al., 2015); 到童年晚期开始避免优势不平等(所得多于他人) (Blake & McAuliffe, 2011)。由此可见, 第三方利他行为的出现说明童年中期(6~11岁)的儿童已经从“对己坚持公平原则”过渡到“对人对己都坚持公平原则” (McAuliffe et al., 2017), 是儿童公平行为发展的重要转折点。

考虑到第三方利他行为对于儿童发展和社会适应的重要性, 有必要深入了解该阶段儿童第三方利他行为的形成机制, 因此本研究选取了10~12岁儿童作为研究对象。10~12岁儿童不仅是处于公平行为发展的重要转折点, 更是处于即将步入青春期的人生关键转折点, 针对这一发展阶段儿童的考察能为引导童年晚期的儿童形成稳定的第三方利他行为提供实证建议。

1.1 儿童的第三方利他行为

第三方惩罚是第三方利他行为的一种方式, 指个体自愿支付成本惩罚违规者的行为, 是人类区别于其他动物的特有社会行动(郭庆科 等, 2016)。以往研究指出即便是婴儿也会表现出第三方惩罚倾向, 例如Meristo和Surian (2014)采用注视时间法发现10月龄的婴儿期待做出公平分配的人和做出不公平分配的人能被区别对待。研究进一步发现2岁儿童已经有赏罚分明的倾向(Hamlin et al., 2011), 3岁的儿童会对违反道德的人做出言语责备(Vaish et al., 2011), 即他们不仅能区别亲社会行为和反社会行为, 而且能在行为上做出区别对待。McAuliffe等人(2015)指出6岁儿童能够对违反公平规范的行为做出系统的、有选择性的干预, 而相比之下5岁儿童的行为模式则仍不明显; 其他研究也证实6到8岁儿童作为第三方时更有意愿做出有代价的惩罚(Gummerum & Chu, 2014; Jordan et al., 2016)。总之, 儿童大致在童年中期会有稳定的第三方惩罚行为, 并且这一结论与国内研究者的发现基本一致。梁福成等(2015)证实中国儿童的公平观念转折年龄在8~10岁, 即在8岁之后对人对己均坚持公平原则, 表现出利他倾向。

除了第三方惩罚, 第三方利他行为还有另一种方式, 即第三方补偿(Leliveld et al., 2012)。第三方补偿指个体自愿支付成本补偿受害者的行为。虽然第三方补偿也是供旁观者采用的利他方式, 对维护公平规范有同等重要的价值, 但是少有研究考察第三方补偿行为(Chavez & Bicchieri, 2013), 更少研究直接考察儿童的第三方补偿行为。已有研究基于实验考察了儿童对两种第三方利他行为的偏好, 并发现相比第三方惩罚, 儿童更喜欢采用第三方补偿的方式来维护公平(Lee & Warneken, 2020)。这一发现在现实情境中也得到证实(Lee et al., 2022)。更多研究考察了成人的第三方利他行为偏好, 却没有得出一致的结论, 即有研究和儿童研究结果一致, 发现第三方补偿行为更受喜欢(Chavez & Bicchieri, 2013; Hu et al., 2016; Leliveld et al., 2012), 也有研究得出相反的结论(Stallen et al., 2018)。不过, 无论是成人还是儿童都对第三方补偿行为(相比第三方惩罚)的评价更高(Dhaliwal et al., 2021; Jordan et al., 2016; Raihani & Bshary, 2015)。Lee和Warneken (2020)指出儿童之所以对第三方补偿者有更高的评价, 是因为他们倾向于认为做出第三方补偿的人是慷慨的、有同情心的, 而认为做出第三方惩罚的人是有攻击性的。

总体而言, 已有研究虽然关注到了儿童对两种第三方利他行为的偏好和评价存在差异, 但这些研究并未直接考察儿童自身的第三方利他行为, 因此我们并不清楚在同一分配情境下儿童分别采用第三方惩罚或第三方补偿时维护公平的力度是否存在差异。深入考察10~12岁儿童对第三方利他行为的偏好是否表现在实际行为上, 有利于了解他们作为第三方的亲社会行为特点, 引导刚形成利他倾向的儿童更主动维护社会规范。现有针对成年人的相关研究在实验中同时设置两种第三方利他方式供旁观者选择一种用于维护公平, 所以旁观者可能会受到选择情境的影响(Jordan et al., 2016)。也就是说, 在这种可选情境下仍旧惩罚而非补偿的人会显得非常有攻击性, 而不是善意的。为了避免这种影响, 本研究分别设置第三方惩罚和第三方补偿两个实验, 考察在同一分配情境下分别采用第三方惩罚和第三方补偿的儿童有怎样的情绪与行为。鉴于相关研究非常少, 本研究只假设可采用的第三方利他方式不同, 儿童的情绪与行为存在差异, 而不做具体假设。

1.2 社会价值取向与第三方利他行为的关系

做出利他行为的第三方考虑了他人利益, 并牺牲自我利益来追求结果的平等性。因此, 第三方利他行为被视为维护公平与社会秩序的亲社会行为(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004; Fehr & Gächter, 2002; Ginther et al., 2016)。大量研究证实了社会价值取向(social value orientation, SVO)和包括利他行为在内的亲社会行为有密切的关系(戚艳艳 等, 2017; 张振 等, 2014)。社会价值取向是个体在相依情境中对自我和他人利益分配的特定偏好, 是相对稳定的人格倾向, 通常分为亲自我取向和亲社会取向(洪慧芳 等, 2012)。亲自我者在社会困境中追求自我利益最大化, 不在意他人利益; 而亲社会者则追求自己与他人的共同利益最大化, 利益差最小化(戚艳艳 等, 2017)。van Lange等人(1997)指出社会价值取向根植于个体与其主要照顾者之间的互动经验, 由儿童早期到青少年期的社会互动模式塑造, 也会受到成年乃至老年期社会经历的影响。Li等人(2013)指出在14岁时中国青少年才形成稳定的社会价值取向, 并且这时的行为能反映其社会价值取向。

虽然已有研究证实社会价值取向对决策的影响, 但少有研究考察社会价值取向对两种第三方利他行为的影响。与此同时, 考虑到10~12岁儿童处于利他行为形成的初期阶段(McAuliffe et al., 2017; 梁福成 等, 2015), 并且其社会价值取向仍未稳定(Li et al., 2013), 了解两者的关系能为教育者更好地引导儿童形成稳定的亲社会取向提供实证支持, 因此更有必要考察社会价值取向对第三方惩罚和第三方补偿行为的影响。鉴于不同社会价值取向的个体面对不公平提议时的反应存在差异(Karagonlar & Kuhlman, 2013), 本研究关注10~12岁儿童在看到公平与不公平的分配提议时, 其社会价值取向如何影响第三方利他行为, 并假设社会价值取向和分配公平性交互影响儿童的第三方利他行为, 即在面对不公平提议时, 亲社会儿童比亲自我儿童做出更多第三方惩罚和补偿行为。

1.3 情绪的中介作用

以往研究大多关注情绪效价对成人第三方利他行为的影响。消极情绪与第三方惩罚行为有关, 如有愤怒情绪的被试会比处于中性情绪的被试提出更高的第三方惩罚金额(Gummerum et al., 2016), 而积极情绪则能正向预测人们的第三方补偿行为(Hao et al., 2016)。Xie等人(2022)发现被优势不公平对待的经历能通过积极情绪来正向预测人们的第三方补偿行为, 而被劣势不公平对待的经历则是通过消极情绪来正向预测人们的第三方惩罚行为。Sanfey等人(2003)还从脑机制层面发现人们的公平决策由情绪和认知两部分组成, 其中对公平的追求对应前脑岛(大脑情绪区域)的活动。而现有的发展研究主要关注情绪效价对儿童资源分配中亲社会行为的影响。陈璟等(2012)在最后通牒博弈任务中采用“高兴与否”测量来让儿童评估自身的情绪效价, 并发现儿童在情绪积极时做出友好的决策, 而情绪消极时则做出有敌意的决策。马英等人(2011)则发现在诱发积极效价的情绪时中小学生会给他人分配更多资源, 而在诱发消极效价的情绪时会给他人分配更少资源。Gummerum等人(2020)也采用“(不)高兴/愉悦”测量来考察情绪效价对9岁儿童第二方惩罚行为的影响, 并发现儿童的不愉悦度与其惩罚力度高度正相关。总之, 情绪效价对不公平情境下的第三方利他行为有重要影响, 但目前仍未有研究直接考察情绪对儿童第三方惩罚和第三方补偿行为的影响。参考相关的儿童情绪研究(陈璟 等, 2012; Gummerum et al., 2020), 且考虑到在情绪词汇中儿童对“高兴”更熟悉(张玮娜, 2011), 本研究采用“(不)高兴”来测量儿童的情绪效价。

1.4 问题提出与假设

本研究的目的是在三种分配情境下考察10~12岁儿童社会价值取向和情绪对第三方利他行为的影响机制以及儿童第三方惩罚和补偿行为的差异。我们设计了两个实验, 分别采用第三方惩罚范式和第三方补偿范式, 以10~12岁儿童为研究对象, 在高度不公平、中度不公平和公平提议三个分配情境下来探讨以下问题: (1)儿童的社会价值取向如何影响其情绪与第三方利他行为?(2)在不公平情境下, 情绪是否在儿童社会价值取向和第三方利他行为的关系中有中介效应?(3)在同一分配情境下, 可以采用的第三方利他方式(惩罚vs.补偿)如何影响儿童的情绪与行为?10~12岁儿童处于基本社会化的关键阶段, 他们刚刚形成利他行为, 并即将形成稳定的社会价值取向, 对其人格倾向、即时情绪和行为表现的综合考察有助于整体了解他们在利益未被影响时如何做出利他行为。另外, 本研究也首次考察了10~12岁儿童的两种第三方利他行为, 为现有研究补充了儿童第三方补偿行为的证据。

基于已有研究和相关理论, 本研究假设: 在公平与不公平情境下儿童社会价值取向对其情绪和第三方利他行为的影响存在差异; 儿童在不公平分配情境下的情绪会中介其社会价值取向与第三方利他行为的关系; 在同一分配情境下采用第三方惩罚的儿童和采用第三方补偿的儿童有情绪与行为上的差异。

2 实验1: 10~12岁儿童社会价值取向对第三方惩罚行为的影响

2.1 实验目的

实验1在第三方惩罚任务中考察社会价值取向对10~12岁儿童第三方利他行为的影响, 提出两个研究假设。研究假设1为社会价值取向与分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与第三方惩罚行为; 研究假设2为在不公平情境下情绪在社会价值取向和第三方惩罚行为中有中介效应。

2.2 实验方法

2.2.1 被试

根据G*Power 3.1的计算, 对于本实验适用的被试间重复测量方差分析, 预计需要的被试量至少为158 (Effect Size = 0.25, α = 0.05, Power = 0.8)。采用随机整群抽样在南京某小学四、五、六年级每个年级抽取两个班, 本实验共招募243名儿童, 由于数据缺失等原因, 剔除10份无效数据。最终实际被试有233人, 其中男生118名, 占比约为51%; 四年级73名(M ± SD = 10.52 ± 0.59岁)、五年级85名(11.36 ± 0.30岁)、六年级75名(12.36 ± 0.26岁); 各年级性别分布不存在显著差异, χ2 (2, n = 233) = 0.672, p = 0.715。主试在实验开始前的指导语和实验过程中会提醒儿童: “在实验中获得的金币多少决定了可以换取多少价值的礼物。”目的是让儿童相信自己的选择与真实的报酬挂钩, 从而做出更真实的选择。但事实上所有参与实验的儿童最终都会得到一件价值为5元人民币的小礼物作为报酬, 可能是笔记本, 也可能是水性笔等其他文具, 由主试随机发放。儿童会拿到不同的小礼物, 但并不知晓每个人的实验报酬都是一样的。所有参与者及其家长在实验前均签署了知情同意书。本研究所有实验程序均通过了中国人民大学心理学系伦理委员会的批准。

2.2.2 实验设计

在分配任务中(以最后通牒博弈为例), Murnighan和Saxon (1998)发现9~12岁美国儿童作为分配者愿意给接受者的比例和作为接受者愿意接受的比例都大概在40%, 而穆岩和苏彦捷(2005)则发现10~12岁中国儿童作为分配者愿意给接受者的比例大概在50%, 作为接受者愿意接受的最低比例约为30%。单一的分配情境对儿童被试而言是否公平可能存在个体差异。因此, 本研究设置了高度不公平、中度不公平和公平3种分配情境, 接受者和分配者所得的比例分别为1∶9、3∶7和5∶5。采用2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的混合实验设计。其中社会价值取向为被试间变量, 分配公平性为被试内变量, 主要因变量为被试的情绪与第三方惩罚行为。

2.2.3 实验材料与流程

被试报告其性别、年龄、年级等基本信息后完成社会价值取向滑块问卷, 接着在高度不公平、中度不公平与公平情境下完成第三方惩罚任务。具体实验材料如下。

社会价值取向滑块问卷 采用社会价值取向滑块问卷(Murphy et al., 2011)测量儿童的社会价值取向。该测验包括两部分, 分别为初级项目和次级项目。本研究只采用初级项目, 包含6道题, 每道题有9个金钱分配方案, 分配对象为自己与他人。被试需要从中做出最偏好的选择。该测验用于计算社会价值取向的度数, 即SVO°。根据公式计算角度, 大于等于22.45°的为亲社会者, 小于22.45°的为亲自我者。计算公式如下:

第三方惩罚任务与情绪测量 采用由独裁者博弈改编的第三方惩罚实验范式, 其中一方为分配者, 另一方为接受者, 被试为第三方旁观者, 并且在实验任务中测量被试的情绪。操作顺序: 告知被试“这里有10枚金币”; 依次呈现分配提议“分配者9/ 7/ 5枚金币, 接受者1/ 3/ 5枚金币”; 参考Gummerum等人(2020), 在7点量表上测量被试看到该分配提议时的情绪效价(从1到7为从“非常不高兴”到“非常高兴”, 4为“平静”); 告知被试“现在你有5枚金币, 这些金币你可以选择全部自己留下, 也可以选择拿出一部分来惩罚分配者”。该惩罚力度定为1∶2, 即被试每拿出1枚金币来惩罚, 分配者就会相应地减少2枚金币(Gummerum & Chu, 2014)。被试明白这一机制后决定拿出多少金币来惩罚分配者。惩罚额度是从0到5的任意整数。三种分配按顺序向所有被试呈现1次, 即高度不公平、中度不公平和公平分配, 被试在分配呈现后需分别报告其情绪与惩罚额度。

为了更便于理解, 我们在中介分析中将“情绪”转换为“不高兴度”, 计算公式为不高兴度= - (情绪- 4)。“不高兴度”从-3到3, 数值越高则表示被试越不高兴, 其中0为平静。

2.3 结果与分析

2.3.1 变量的描述性统计

该实验的被试中有156名亲社会者(51.3%为女生), 77名亲自我者(45.5%为女生), 亲社会与亲自我者的性别分布不存在显著差异, χ2 (1, n = 233) = 0.700, p = 0.403。其他变量的描述性统计结果见表1。

表1 描述性统计结果

| 变量 | 实验1 第三方惩罚任务(n = 233) | 实验2 第三方补偿任务(n = 238) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M / % | SD | M / % | SD | |

| 性别(男生) | 50.6% | — | 50.4% | — |

| 年龄(岁) | 11.42 | 0.84 | 11.43 | 0.87 |

| 社会价值取向(亲自我者) | 33% | — | 26.5% | — |

| 社会价值取向度数 | 27.33 | 17.52 | 28.70 | 14.27 |

| 高度不公平情绪 | 2.15 | 1.20 | 2.36 | 1.33 |

| 高度不公平拿出金币数 | 2.68 | 1.60 | 2.77 | 1.38 |

| 中度不公平情绪 | 3.03 | 0.95 | 3.24 | 1.03 |

| 中度不公平拿出金币数 | 1.60 | 1.14 | 1.79 | 1.13 |

| 公平情绪 | 5.46 | 1.35 | 5.00 | 1.25 |

| 公平拿出金币数 | 0.24 | 0.85 | 0.47 | 1.14 |

注: “拿出金币数”指被试的第三方惩罚金额(实验1)或第三方补偿金额(实验2)。

2.3.2 社会价值取向与分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与第三方惩罚行为

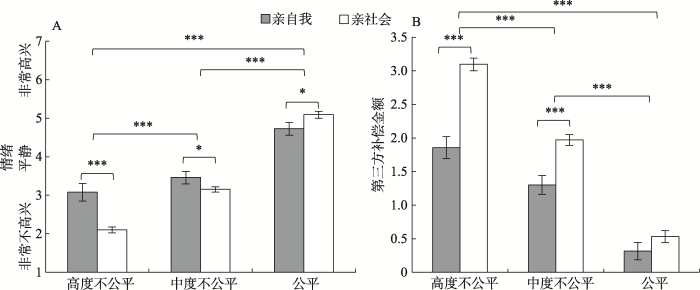

被试面对不同公平性的分配提议时的情绪与其作为第三方对分配者的惩罚意愿相关。将被试的情绪作为因变量, 进行2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果显示分配公平性的主效应显著, F(1, 306) = 411.48, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.64, 在高度不公平情境下儿童情绪最消极, 而在公平情境下情绪最积极; 社会价值取向的主效应不显著, F(1, 231) = 1.64, p = 0.202; 社会价值取向与分配公平性的交互效应显著, F(1, 306) = 4.10, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.02。简单效应分析表明, 在高度不公平的情境下亲社会者的情绪显著比亲自我者的更消极(2.02 ± 1.09 vs. 2.43 ± 1.39, p = 0.014), 在中度不公平与公平两个情境下两者无显著差异(p > 0.1), 如图1(A)所示。

图1

图1

不同分配情境下亲自我与亲社会儿童的情绪(A)与第三方惩罚金额(B)

注: 图中的误差棒(error bar)表示标准误; † p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, 下同

被试愿意拿出多少金币用于惩罚反映其作为第三方对分配者的惩罚程度。将被试的惩罚金额作为因变量, 进行2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果显示分配公平性的主效应显著, F(2, 360) = 280.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.55, 在高度不公平情境下儿童惩罚金额最高, 而在公平情境下惩罚金额最低; 社会价值取向的主效应显著, F(1, 231) = 7.32, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.03; 分配公平性与社会价值取向的交互效应显著, F(2, 360) = 11.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05。简单效应分析表明, 在高度不公平的情境下亲社会者的惩罚金额显著高于亲自我者的(2.96 ± 1.44 vs. 2.13 ± 1.77, p = 0.014), 在中度不公平的情境下亲社会者的惩罚金额仅边缘显著高于亲自我者的(1.70 ± 1.04 vs. 1.40 ± 1.30, p = 0.061), 如图1(B)所示。

2.3.3 情绪的中介效应

表2 回归分析结果(情绪在社会价值取向与第三方利他行为之间的中介效应检验)

| 自变量 | 实验1 高度不公平 | 实验2 高度不公平 | 实验2 中度不公平 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 第三方惩罚 | 不高兴度 | 第三方惩罚 | 第三方补偿 | 不高兴度 | 第三方补偿 | 第三方补偿 | 不高兴度 | 第三方补偿 | |

| 模型1 | 模型2 | 模型3 | 模型4 | 模型5 | 模型6 | 模型7 | 模型8 | 模型9 | |

| SVO° | 0.27*** | 0.17** | 0.21*** | 0.50*** | 0.44*** | 0.41*** | 0.40*** | 0.18** | 0.37*** |

| 不高兴度 | 0.34*** | 0.20** | 0.18** | ||||||

| 年龄 | -0.15* | -0.20** | -0.08 | -0.10 | -0.20*** | -0.06 | -0.08 | -0.12 | -0.06 |

| 性别 | -0.27* | -0.12 | -0.23 | -0.03 | 0.14 | -0.05 | -0.00 | 0.03 | -0.01 |

| F | 8.29*** | 4.84** | 15.09*** | 26.64*** | 21.71*** | 23.45*** | 14.90*** | 3.62* | 13.64*** |

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| 调整后R2 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

注: SVO°为社会价值取向度数; 性别为哑变量, 1=男, 2=女; 实验2中度不公平情境(模型7, 8和9)中不高兴度未通过中介效应检验; 模型1和4对应中介效应的路径c; 模型2和5对应中介效应的路径a; 模型3和6对应中介效应的路径b和c’。

结果表明以社会价值取向为预测变量, 第三方惩罚行为为结果变量的回归方程通过了显著性检验, F(3, 229) = 8.29, p < 0.001; 以社会价值取向和不高兴度为预测变量, 第三方惩罚行为为结果变量的回归方程也通过了显著性检验, F (4, 228) = 15.09, p < 0.001。在高度不公平情境下, 社会价值取向可以正向预测不高兴度(β = 0.17, t = 2.63, p = 0.009), 不高兴度正向预测儿童的第三方惩罚行为(β = 0.34, t = 5.67, p < 0.001)。协变量年龄和性别在中介模型中对第三方惩罚行为没有显著影响。中介效应检测结果详见附录表S2, 中介效应路径如图2所示。

图2

高度不公平情境下, 不高兴度的间接效应值为0.06, 其95%置信区间[0.01,0.11]不包含0, 说明该间接效应显著; 社会价值取向对第三方惩罚行为的直接效应值为0.21, 其95%置信区间[0.09,0.33]不包含0, 说明该直接效应显著。结果表明情绪的中介效应占总效应比例为21.6%, 即儿童的社会价值取向越亲社会, 在高度不公平情境下就越不高兴, 进而增加第三方惩罚行为。

3 实验2: 10~12岁儿童社会价值取向对第三方补偿行为的影响

3.1 实验目的

第三方利他行为不仅有第三方惩罚, 还有第三方补偿。为了进一步了解儿童的第三方利他行为, 实验2招募了另一批10~12岁儿童被试参加第三方补偿任务。为了在第三方补偿任务中考察社会价值取向、情绪对10~12岁儿童利他行为的影响, 并且对比两种第三方利他方式下儿童表现的差异, 我们提出三个假设。研究假设3为社会价值取向与分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与第三方补偿行为; 研究假设4为在不公平情境下, 情绪在社会价值取向和第三方补偿行为中有中介效应; 研究假设5为采用不同第三方利他方式的儿童在同一分配情境下的情绪与行为有差异。

3.2 实验方法

3.2.1 被试

根据G*Power 3.1的计算, 对于本实验适用的被试间重复测量方差分析, 预计需要的被试量至少为158 (Effect Size = 0.25, α = 0.05, Power = 0.8)。采用随机整群抽样在南京某小学四、五、六年级每个年级抽取两个班, 本实验共招募241名儿童, 由于缺失值等原因, 剔除3份无效数据。最终实际被试有238人, 其中男生120名, 占比约为50%; 四年级68名(10.35 ± 0.34岁)、五年级85名(11.34 ± 0.29岁)、六年级75名(12.41 ± 0.27岁); 各年级性别分布不存在显著差异, χ2 (2, n = 238) = 0.341, p = 0.843。

3.2.2 实验设计

采用2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的混合实验设计。主要因变量为被试的情绪与第三方补偿行为。

3.2.3 实验程序

实验1与实验2的流程与材料基本一致, 区别在于实验1为第三方惩罚任务, 被试拿出金币用于惩罚分配者; 而实验2为第三方补偿任务, 被试拿出金币用于补偿接受者。在后续分析中, 实验1的第三方惩罚金额与实验2的第三方补偿金额被概括为第三方利他金额。虽然两种第三方利他金额的作用对象分别是分配者和接受者, 发挥的具体功能不同, 但整体而言它们都能衡量被试以个人资源为代价来维护公平的行为。

3.3 结果与分析

3.3.1 变量的描述性统计

该实验的被试中有175名亲社会者(49.1%为女生), 63名亲自我者(50.8%为女生), 亲社会者与亲自我者的性别分布不存在显著差异, χ2 (1, n = 238) = 0.050, p = 0.822。其他变量的描述性统计结果见表1。

3.3.2 社会价值取向与分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与第三方补偿行为

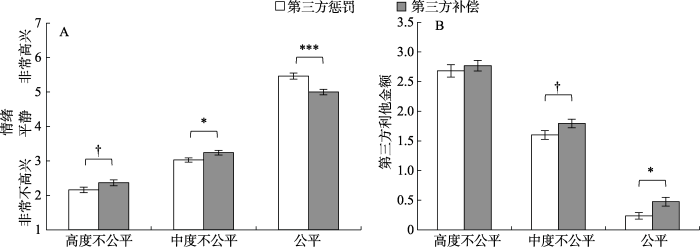

被试面对不同公平性的分配提议时的情绪与其作为第三方对接受者的补偿意愿相关。将被试的情绪作为因变量, 进行2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果表明社会价值取向的主效应显著, F (1, 236) = 8.08, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.03; 分配公平性的主效应显著, F(1, 339) = 203.79, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.46, 在高度不公平情境下儿童情绪最消极, 而在公平情境下情绪最积极; 社会价值取向与分配公平性的交互效应显著, F (1, 339) = 16.16, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06。简单效应分析表明, 在高度不公平情境下亲社会者的情绪显著比亲自我者的更消极(2.10 ± 1.01 vs. 3.08 ± 1.80, p < 0.001), 在中度不公平情境下亲社会者的情绪显著比亲自我者的更消极(3.15 ± 0.92 vs. 3.46 ± 1.28, p = 0.043), 在公平情境下亲社会者的情绪显著比亲自我者的更积极(5.09 ± 1.21 vs. 4.73 ± 1.33, p = 0.049), 如图3(A)所示。

图3

被试愿意拿出多少金币反映其作为第三方对接受者的补偿程度。将被试的补偿金额作为因变量, 进行2 (社会价值取向: 亲社会, 亲自我) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果表明社会价值取向的主效应显著, F(1, 236) = 26.01, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10; 分配公平性的主效应显著, F(2, 394) = 280.10, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.54, 在高度不公平情境下儿童补偿金额最高, 而在公平情境下补偿金额最低; 分配公平性与社会价值取向的交互效应显著, F (2, 394) = 17.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07。简单效应分析表明, 在高度不公平情境下亲社会者的补偿金额显著高于亲自我者的(3.10 ± 1.25 vs. 1.86 ± 1.31, p < 0.001); 在中度不公平情境下亲社会者的补偿金额也显著高于亲自我者的(1.97 ± 1.08 vs. 1.30 ± 1.12, p < 0.001); 而公平情境下两者差异不显著(p > 0.1), 如图3(B)所示。

3.3.3 情绪的中介效应

中介分析思路同实验1, 根据实验2所有变量的相关分析结果(详见附录表S3), 两种不公平分配情境下社会价值取向、不高兴度和第三方补偿行为都满足中介分析的前提, 因此后续分别检验高度不公平和中度不公平情境下情绪的中介效应。分析前将所有变量标准化。各变量间的回归关系分析结果如表2所示。

结果表明在高度不公平情境下, 以社会价值取向为预测变量, 第三方补偿行为为结果变量的回归方程通过了显著性检验, F(3, 234) = 26.64, p < 0.001; 以社会价值取向和不高兴度为预测变量, 第三方补偿行为为结果变量的回归方程也通过了显著性检验, F(4, 233) = 23.45, p < 0.001。在高不公平情境下, 社会价值取向可以正向预测不高兴度(β = 0.44, t = 7.49, p < 0.001), 不高兴度正向预测儿童的第三方补偿行为(β = 0.20, t = 3.26, p = 0.001)。协变量年龄和性别在中介模型中对第三方补偿行为没有显著影响。而中度不公平情境下虽然各个变量之间的回归关系都通过了显著性检验, 但根据中介效应检验结果情绪没有发挥显著的中介作用。中介效应检测结果详见附录表S4, 中介效应路径如图4所示。

图4

高度不公平情境下, 不高兴度的间接效应值为0.09, 其95%置信区间[0.02,0.16]不包含0, 说明该间接效应显著; 社会价值取向对第三方惩罚行为的直接效应值为0.41, 其95%置信区间[0.29,0.53]不包含0, 说明该直接效应显著。结果表明不高兴度的中介效应占总效应比例为18%, 即儿童的社会价值取向越亲社会, 在高度不公平情境下就越不高兴, 进而增加第三方补偿行为。

3.3.4 第三方利他方式影响儿童的第三方情绪与行为

为了考察第三方利他方式对儿童情绪和行为的影响, 我们比较了实验1 (即第三方惩罚组)和实验2 (即第三方补偿组)被试在对应分配情境下的情绪与第三方利他行为。首先, 将社会价值取向、性别、年龄等作为因变量, 独立样本t检验结果表明第三方惩罚组与第三方补偿组的被试在以上变量中都没有显著差异。

将被试的情绪作为因变量, 进行2 (第三方利他方式: 惩罚, 补偿) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果表明第三方利他方式的主效应不显著, F(1, 469) = 0.06, p = 0.812; 分配公平性的主效应显著, F(1, 646) = 795.37, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63, 在高度不公平情境下儿童情绪最消极, 而在公平情境下情绪最积极; 第三方利他方式与分配公平性的交互效应显著, F (1, 646) = 12.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03。简单效应分析表明在两种不公平情境下, 第三方补偿组被试的情绪比第三方惩罚组的更积极, 在高度不公平情境下差异边缘显著(2.36 ± 1.33 vs. 2.15 ± 1.20, p = 0.078), 在中度不公平情境下差异在统计上达到显著(3.24 ± 1.03 vs. 3.03 ± 0.95, p = 0.023)。然而, 在公平分配情境下第三方补偿组被试的情绪却比第三方惩罚组的更消极, 这种差异在统计上达到显著(5.00 ± 1.25 vs. 5.46 ± 1.35, p < 0.001)。这说明当可采用的第三方利他方式为补偿时, 儿童更认为公平分配是合理的, 因此情绪波动比第三方惩罚组的更小, 如图5(A)所示。

图5

将被试拿出金币数作为因变量, 进行2 (第三方利他方式: 惩罚, 补偿) × 3 (分配公平性: 高度不公平, 中度不公平, 公平)的重复测量方差分析, 结果表明第三方利他方式的主效应边缘显著, F(1, 469) = 3.83, p = 0.051, ηp2 = 0.01, 第三方补偿组的利他金额相比第三方惩罚组的更高(1.68 ± 0.06 vs. 1.51 ± 0.06); 分配公平性的主效应显著, F(2, 740) = 754.91, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.62, 在高度不公平情境下儿童第三方利他金额最高, 而在公平情境下第三方利他金额最低; 第三方利他方式与分配公平性的交互效应不显著, F(2, 740) =0.82, p = 0.417。结果表明相比第三方惩罚组, 第三方补偿组被试在三种分配情境下拿出的金币在数量上都更多。具体而言, 在中度不公平条件下第三方补偿组被试拿出的金币数量高于第三方惩罚组的, 在统计上边缘显著(1.79 ± 1.13 vs. 1.60 ± 1.14, p = 0.065); 在公平条件下第三方补偿组被试拿出的金币数量在统计上显著高于第三方惩罚组的(0.47 ± 1.14 vs. 0.24 ± 0.85, p = 0.011), 如图5(B)所示。

综合以上分析, 在情绪上, 第三方补偿组的儿童(相比第三方惩罚组)面对不同公平程度的分配时情绪波动更小; 在行为上, 第三方补偿组的儿童(相比第三方惩罚组)在不公平情境下会拿出更多金币来维护公平。由此可见, 第三方利他方式影响10~12岁儿童面对同一分配提议时的情绪与行为。

4 讨论

实验1结果显示在第三方惩罚任务中, 社会价值取向与分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与惩罚金额, 研究假设1成立。具体而言, 在高度不公平的情境下亲社会儿童的情绪比亲自我儿童的更消极, 并且亲社会儿童的惩罚金额高于亲自我儿童的。实验1结果还显示在高度不公平情境下, 情绪在社会价值取向和第三方惩罚的关系中发挥中介作用, 而在中度不公平情境下并未发现情绪的中介效应, 研究假设2部分成立。

实验2结果显示在第三方补偿任务中, 社会价值取向和分配公平性交互影响儿童的情绪与补偿金额, 研究假设3成立。具体而言, 三种分配情境下亲社会者与亲自我者的情绪都有差异, 并且在高度与中度不公平情境下亲社会者的补偿金额都会高于亲自我者的。实验2结果还显示在高度不公平情境下, 情绪在社会价值取向和第三方补偿的关系中发挥中介作用, 但其他情境下情绪没有中介效应, 研究假设4部分成立。

我们进一步发现当可采用的第三方利他方式不同时, 10~12岁儿童面对同一分配时情绪与行为存在差异, 研究假设5成立。对比实验1与实验2的被试在同一分配情境下的情绪与拿出金币数, 发现当可采用的第三方利他行为是补偿时(相比惩罚), 儿童面对不同分配提议时情绪波动更小, 但在中度不公平情境下会拿出更多金币来维护公平。

4.1 社会价值取向(亲社会vs.亲自我)影响儿童的第三方利他行为

实验1发现在第三方惩罚任务中, 在高度不公平的情境下亲社会儿童才会比亲自我儿童更不高兴, 并且亲社会儿童的惩罚金额高于亲自我儿童的, 而在中度不公平和公平情境下儿童的情绪和第三方惩罚行为没有明显差异。而实验2发现在第三方补偿任务中, 三种分配情境下亲社会儿童与亲自我儿童的情绪都有差异, 其中在高度与中度不公平情境下亲社会儿童比亲自我儿童更不高兴, 并且亲社会儿童的第三方补偿金额也高于亲自我儿童的。在公平情境下亲社会儿童比亲自我儿童更高兴, 第三方补偿金额没有明显差异。

总体而言, 实验1与实验2的结果证实了社会价值取向会影响儿童的第三方利他行为, 并且公平与不公平情境下社会价值取向对儿童第三方利他行为的影响有差异, 即相比亲自我儿童, 亲社会儿童会在不公平情境下做出更多第三方惩罚与第三方补偿行为。这些结果证实了Schwartz (1977)提出的社会规范激活理论, 即10~12岁儿童的两种第三方利他行为都取决于个体的社会价值取向和情境的分配公平性。这也再次证实了到童年晚期, 儿童对人对己都大致形成了公平原则, 并且亲社会儿童的公平原则更为稳定。

4.2 情绪在高度不公平情境下发挥中介效应

社会价值取向影响儿童在高度不公平情境下的情绪。在实验1和实验2中, 社会价值取向越是亲社会的儿童在看到高度不公平提议时越不高兴。这证实了亲社会儿童相比亲自我儿童更关注“公平”, 而非个人利益。即便高度不公平提议并不会影响到亲社会儿童本身的利益, 他们还是不高兴。实验1和实验2也一致表明社会价值取向越是亲社会的儿童看到高度不公平提议时越不高兴, 进而做出越多的第三方利他行为。这一发现在儿童群体中证实了情绪不仅在与自身利益相关的公平决策中有重要作用(Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996; Sanfey et al., 2003), 而且在与自身利益不相关的第三方利他决策中也扮演重要的角色。其中不高兴度(即情绪)不仅可以预测儿童的第三方惩罚行为, 还能预测儿童的第三方补偿行为。Fehr和Schmidt (1999)最早提出了“不公平厌恶”, 认为人们在面对不公平情境时会产生厌恶情绪。梁福成等人(2015)也基于社会效用模型指出: 相比自己所得多于他人(优势不公平分配), 人们会对自己与他人所得相同的分配(公平分配)更满意。我们的发现与以往研究共同揭示了不公平提议影响儿童的情绪, 因此儿童会通过第三方利他等方式来维护公平, 平衡消极情绪。这一结果进一步支持了社会规范激活理论, 并且再次从行为层面证实了决策领域的“认知−情绪”双系统模型。根据Reno等人(1993), 第三方惩罚任务和第三方补偿任务让儿童看到他人破坏或维护社会规范的行为, 并从认知和情绪层面共同激活儿童的社会规范。以往研究强调第三方惩罚任务激发个体的特定情绪(如愤怒), 进而个体做出利他行为(陈思静 等, 2015)。本研究证实情绪对第三方利他行为的作用机制不局限于某一特定情绪类型, 不同的情绪效价也会对第三方利他行为有明显的作用。

另外, 我们认为之所以情绪的中介效应只出现在高度不公平情境下而不存在于中度不公平情境下, 可能是因为儿童作为利益无关的第三方, 中度不公平的分配提议对于他们而言仍在可以接受的范围内, 只有在极度不公平的情况下才会有明显的情绪波动。

4.3 儿童的情绪与行为因可采用的第三方利他方式不同(惩罚vs.补偿)而存在差异

我们对比第三方惩罚组和第三方补偿组被试在同一分配情境下的情绪与拿出金币数, 结果显示第三方补偿组的儿童面对不同分配提议时情绪波动更小, 但在中度不公平情境下会比第三方惩罚组儿童拿出更多金币来维护公平。这一发现在儿童群体中再次证实了第三方惩罚和第三方补偿不是完全对等的。

我们认为儿童在不同第三方利他方式上的情绪差异可能是由于两种方式对应的内在动机(威慑vs.公正关怀)对积极情绪和消极情绪的激发存在差异。从心理机制来看第三方惩罚和第三方补偿虽然都是有代价的第三方利他行为, 但这两种行为并不完全相等。第三方惩罚行为的内在动机是威慑和报复(Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith et al., 2002), 能降低目前的不公平感, 也能减少未来不公平的发生(Wenzel & Thielmann, 2006); 而第三方补偿行为的内在动机是公正关怀, 能降低不公平感, 但无法减少不公平的发生率(Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith et al., 2002)。另外, 我们还认为情绪差异可能是由于两种利他方式对应的角色和权力不同导致的。我们在规定儿童被试采用某种第三方利他方式来维护公平时, 便赋予了他们对应的角色和权力。第三方惩罚组的儿童被赋予了惩罚违规者的权力, 第三方补偿组的儿童则被赋予了补偿受害者的权力。先前研究提出第三方惩罚不仅惩罚违规者, 还维护了社会秩序, 而相较之下第三方补偿没有维护社会秩序的直接作用(Chavez & Bicchieri, 2013)。所以被赋予第三方惩罚的儿童权力更大, 因此可能有更强的责任感, 在看到不公平提议时表现出更强的不公平厌恶, 情绪波动更大。

而第三方惩罚组和第三方补偿组儿童的行为差异可能是由于中度不公平情境并未危及儿童本身的利益, 并且也不至于引发儿童威慑他人的动机, 因此相比较下第三方补偿组的儿童做出了更多的利他行为。另外, 间接互惠理论和科尔伯格的道德认知发展理论也能解释这种差异。根据间接互惠理论, 人们做出第三方利他行为来维护公平规范, 从而在群体中建立良好的声誉, 进而在将来与他人互动时也能得到公平对待(Nowak, 2006)。从间接获益的角度来看, 第三方补偿行为相比之下能获得更好的声誉(Jordan et al., 2016)。根据科尔伯格的道德认知发展理论(Kohlberg & Kramer, 1969), 10~12岁儿童处于习俗水平; 这一水平包含两个阶段, 即寻求认可阶段和服从权威阶段, 而这个年龄段的儿童正处于寻求认可阶段, 他们会为了声誉和人际关系而做出亲社会行为(Eisenberg et al., 2006)。因此, 10~12岁儿童做出更多的第三方补偿行为不仅是为了维护公平, 还可能是为了获得认可与称赞。

4.4 研究创新与局限

本研究首次在10~12岁儿童群体中考察了社会价值取向对两种第三方利他行为的影响机制, 并且发现了情绪在高度不公平情境下发挥中介作用。这一结果支持了社会规范激活理论, 且扩展了该理论适用的范围, 说明该理论既能解释第三方惩罚行为, 又能很好地描述第三方补偿行为的形成机制。10~12岁儿童处于利他行为形成的初期阶段(梁福成 等, 2015; McAuliffe et al., 2017), 并且其社会价值取向仍未稳定(Li et al., 2013), 但在公平规范被高度违反的情况下仍未稳定的社会价值取向也对第三方利他行为有明显的作用。这一结果说明即便这一阶段的儿童希望获得认可与称赞, 亲社会取向的儿童(相比亲自我儿童)还会在中度不公平的情境下做出更多的第三方惩罚行为, 再次强调了亲社会取向的重要性。这提示10~12岁儿童的教师与家长可以通过称赞儿童的亲社会行为、构建亲社会的学习与生活氛围等方式, 来引导儿童形成稳定的亲社会取向。如果社会中的每一个人都具有稳定的亲社会取向, 那么每当违反社会规范的现象出现时, 违规者都会受到惩罚, 受害者都会得到补偿, 社会会因此井然有序。

本研究不仅与以往研究一样考察了儿童的第三方惩罚行为, 而且还考察了儿童的第三方补偿行为, 从发展的角度为两种行为的差异提供证据。我们分别考察儿童的两种行为, 却发现即便是排除选择情境的影响(Jordan et al., 2016), 儿童还是会做出更多的第三方补偿行为, 即第三方补偿组的儿童在中度不公平情境下维护规范的力度强于第三方惩罚组的。这再一次证实人类对第三方补偿的偏好具有稳定性(van Doorn et al., 2018)。从现实层面上, 这一结果也启示10~12岁儿童的教师与家长要更多地赞许儿童的第三方惩罚行为, 让儿童认识到“惩罚”虽然看起来不友好, 但对违反公平规范行为的惩罚能维护社会秩序, 是一种值得推崇的行为。虽然儿童偏好的第三方补偿也是一种维护公平的方式, 但从效果来看, 第三方惩罚相比第三方补偿具有更好的维护公平效果(Chavez & Bicchieri, 2013), 所以即便儿童偏好第三方补偿的方式, 也有必要培养儿童做出更多第三方惩罚行为, 让他们勇于惩罚违规者。

虽然本研究获得了一些有意义的发现, 但也存在一些局限。首先, 对于被试而言, 他们可采用的第三方利他方式是单一的, 只能决定是否拿出金币与拿出多少金币, 而不能选择用什么方式来维护公平, 这虽然避免了选择情境的影响, 但还是无法直接回答“儿童更倾向于以哪种第三方利他方式来维护公平”。其次, 本研究只设置了单一的第三方惩罚任务和第三方补偿任务, 没有设置第三方惩罚与补偿任务, 即被试可以在惩罚分配者的同时也补偿接受者, 未来研究也可以进一步探讨更复杂的第三方利他行为。另外, 本研究利用情境实验问卷来对童年晚期的被试展开调查, 以金币分配作为情境, 但这种情境难以完全复制儿童在现实生活中遇到的社会困境, 因此未来研究可以使用更多生活化的情境来提高研究结论的生态效度。

5 结论

(1) 10~12岁儿童的社会价值取向大多为亲社会, 且社会价值取向会影响儿童的第三方利他行为;

(2)当可采用的第三方利他方式为惩罚时, 亲社会儿童(相比亲自我儿童)在高度不公平情境下拿出更多金币用于维护公平, 情绪在其中发挥中介作用;

(3)当可采用的第三方利他方式为补偿时, 亲社会儿童(相比亲自我儿童)在高度不公平和中度不公平情境下拿出更多金币用于维护公平, 情绪只在高度不公平情境下发挥中介作用;

(4)同一分配情境下儿童的情绪与行为因可采用的第三方利他方式而不同, 即当可采用的第三方利他行为是补偿时(相比惩罚), 儿童面对不同分配提议时情绪波动更小, 但在中度不公平情境下拿出更多金币来维护公平。

附录

附表S1 实验1相关分析结果

| 变量 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 社会价值取向度数 | ||||||||

| 2 | 高度不公平情绪 | -0.136* | |||||||

| 3 | 高度不公平拿出金币数 | 0.241*** | -0.393*** | ||||||

| 4 | 中度不公平情绪 | -0.081 | 0.636*** | -0.307*** | |||||

| 5 | 中度不公平拿出金币数 | 0.126 | -0.251*** | 0.668*** | -0.289*** | ||||

| 6 | 公平情绪 | 0.098 | -0.311*** | 0.323*** | -0.174** | 0.212** | |||

| 7 | 公平拿出金币数 | -0.068 | 0.288*** | 0.049 | 0.179** | 0.263*** | -0.233*** | ||

| 8 | 年龄 | 0.165* | 0.178** | -0.113 | 0.181** | 0.016 | -0.215** | 0.093 | |

| 9 | 性别 | 0.044 | 0.052 | -0.121 | 0.091 | -0.099 | -0.062 | -0.113 | -0.004 |

附表S2 实验1高度不公平情境下情绪的间接效应检验结果

| 效应 | 效应量 | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 直接效应 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| 间接效应 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| 总效应 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.40 |

附表S3 实验2相关分析结果

| 变量 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 社会价值取向度数 | ||||||||

| 2 | 高度不公平情绪 | -0.417*** | |||||||

| 3 | 高度不公平拿出金币数 | 0.494*** | -0.385*** | ||||||

| 4 | 中度不公平情绪 | -0.172** | 0.563*** | -0.300*** | |||||

| 5 | 中度不公平拿出金币数 | 0.392*** | -0.273** | 0.699*** | -0.245*** | ||||

| 6 | 公平情绪 | 0.206** | -0.296*** | 0.206** | 0.017 | 0.167** | |||

| 7 | 公平拿出金币数 | 0.167** | -0.317*** | 0.317*** | -0.034 | 0.486*** | -0.002 | ||

| 8 | 年龄 | 0.065 | 0.241*** | -0.075 | 0.115 | -0.055 | -0.144* | 0.020 | |

| 9 | 性别 | -0.061 | -0.036 | -0.047 | 0.002 | -0.028 | 0.145* | -0.111 | 0.040 |

附表S4 实验2不公平情境下情绪的间接效应检验结果

| 分配情境 | 效应 | 效应量 | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 高度不公平 | 直接效应 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.53 |

| 间接效应 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.17 | |

| 总效应 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.61 | |

| 中度不公平 | 直接效应 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.48 |

| 间接效应 | 0.03 | 0.03 | -0.003 | 0.09 | |

| 总效应 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.52 |

参考文献

"I had so much it didn't seem fair": Eight-year-olds reject two forms of inequity

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.006

URL

PMID:21616483

[本文引用: 1]

Research using economic games has demonstrated that adults are willing to sacrifice rewards in order to prevent inequity both when they receive less than a social partner (disadvantageous inequity) and when they receive more (advantageous inequity). We investigated the development of both forms of inequity aversion in 4- to 8-year-olds using a novel economic game in which children could accept or reject unequal allocations of candy with an unfamiliar peer. The results showed that 4- to 7-year-olds rejected disadvantageous offers, but accepted advantageous offers. By contrast, 8-year-olds rejected both forms of inequity. These results suggest that two distinct mechanisms underlie the development of the two forms of inequity aversion.Copyright © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

The ontogeny of fairness in seven societies

DOI:10.1038/nature15703 URL [本文引用: 1]

The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.007 URL [本文引用: 2]

Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.284

URL

PMID:12150228

[本文引用: 2]

One popular justification for punishment is the just deserts rationale: A person deserves punishment proportionate to the moral wrong committed. A competing justification is the deterrence rationale: Punishing an offender reduces the frequency and likelihood of future offenses. The authors examined the motivation underlying laypeople's use of punishment for prototypical wrongs. Study 1 (N = 336) revealed high sensitivity to factors uniquely associated with the just deserts perspective (e.g., offense seriousness, moral trespass) and insensitivity to factors associated with deterrence (e.g., likelihood of detection, offense frequency). Study 2 (N = 329) confirmed the proposed model through structural equation modeling (SEM). Study 3 (N = 351) revealed that despite strongly stated preferences for deterrence theory, individual sentencing decisions seemed driven exclusively by just deserts concerns.

Third-party sanctioning and compensation behavior: Findings from the ultimatum game

DOI:10.1016/j.joep.2013.09.004 URL [本文引用: 4]

The development of ultimatum game decision-making with complete information in children

Developmental tendency and characters of Ultimatum game decision making with complete information were examined among 4-12 years old children and 40 adults, and the role of emotion during Ultimatum decision making was explored primarily. The results showe

儿童完全信息最后通牒博弈决策的发展

考查了200名4-12岁儿童及40名成人完全信息最后通牒博弈决策的发展趋势与特点,并对情绪在最后通牒博弈决策中的作用做了初步探索。结果表明:(1)完全信息最后通牒任务中,作为分配者时4-6岁儿童更多提出小于半数的要约,而9-12岁儿童和成人则更多地提出平等分配的要约。作为应答者时儿童和成人均接受大部分要约。(2)公平策略和权宜策略是儿童与成人分配者采取的主要策略,而儿童与成人应答者则主要采用权宜策略。(3)基于满意与否的情绪体验是儿童应答者是否行使否决权的直接动力。

The influence of third-party punishment on cooperation: An explanation of social norm activation

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.00389

[本文引用: 2]

<p>Third-party punishment (TPP) plays an important role in both improving cooperation and maintaining social norms. However, Cognitive Evaluation Theory suggests that TPP may also negatively affect cooperation, because TPP reduces the internal motivation of cooperative behaviors. Therefore, the influence of TPP on cooperation may have two different manifestations depending on the specific kind of activated social norms — descriptive norms (what most people actually do) or injunctive norms (what people should do). This study used two experiments to examine the influence of TPP on cooperation. Experiment 1 analyzed the effects of the two different social norms on cooperation without TPP. The subjects (120 university students) participated in a two-round Dictator Game, which used a 2 (high/low descriptive norms) by 2 (high/low injunctive norms) between-subjects design. Experiment 2 (with 300 university students) examined the influence of different TPP frequencies on cooperation. The subjects participated in a four-round Dictator Game with a third-party member who could punish both the dictator and the receiver in Round 2 and 3. In Round 3, the subjects were informed the frequency of TPP (a between-subjects factor), which were controlled by the experimenter on 10 levels ranging from 0% to 90%. The result showed that descriptive norms had a more significant influence in comparison to injunctive norms, and there was a significant interaction between the two types of norms. Descriptive norms played a more important role on cooperation when there was no punisher, whereas injunctive norms' effect on cooperation was stronger when there was a punisher. The results also implied that a low frequency of TPP could successfully increase the level of cooperation, even when the punishment sanction was removed. We also found that higher frequency of TPP reduced the internal motivation on cooperation. An explanation of these effects was that TPP could not only remind subjects of the injunctive norms but also the existence of norm violation. When the perception of norm violation increased with higher frequency of TPP, the perception of descriptive norms decreases and so do cooperative behaviors.</p>

第三方惩罚对合作行为的影响: 基于社会规范激活的解释

Are irrational reactions to unfairness truly emotionally-driven? dissociated behavioural and emotional responses in the ultimatum game task

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.09.001

URL

PMID:19786275

[本文引用: 1]

The "irrational" rejections of unfair offers by people playing the Ultimatum Game (UG), a widely used laboratory model of economical decision-making, have traditionally been associated with negative emotions, such as frustration, elicited by unfairness (Sanfey, Rilling, Aronson, Nystrom, & Cohen, 2003; van't Wout, Kahn, Sanfey, & Aleman, 2006). We recorded skin conductance responses as a measure of emotional activation while participants performed a modified version of the UG, in which they were asked to play both for themselves and on behalf of a third-party. Our findings show that even unfair offers are rejected when participants' payoff is not affected (third-party condition); however, they show an increase in the emotional activation specifically when they are rejecting offers directed towards themselves (myself condition). These results suggest that theories emphasizing negative emotions as the critical factor of "irrational" rejections (Pillutla & Murninghan, 1996) should be re-discussed. Psychological mechanisms other than emotions might be better candidates for explaining this behaviour.

Reputational and cooperative benefits of third-party compensation

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.01.003 URL [本文引用: 1]

Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis

DOI:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

URL

PMID:17402809

[本文引用: 1]

Studies that combine moderation and mediation are prevalent in basic and applied psychology research. Typically, these studies are framed in terms of moderated mediation or mediated moderation, both of which involve similar analytical approaches. Unfortunately, these approaches have important shortcomings that conceal the nature of the moderated and the mediated effects under investigation. This article presents a general analytical framework for combining moderation and mediation that integrates moderated regression analysis and path analysis. This framework clarifies how moderator variables influence the paths that constitute the direct, indirect, and total effects of mediated models. The authors empirically illustrate this framework and give step-by-step instructions for estimation and interpretation. They summarize the advantages of their framework over current approaches, explain how it subsumes moderated mediation and mediated moderation, and describe how it can accommodate additional moderator and mediator variables, curvilinear relationships, and structural equation models with latent variables.(c) 2007 APA, all rights reserved.

The influence of emotion and social value orientations on distributional fairness

情绪、社会价值取向对分配公平观的影响

Third-party punishment and social norms

DOI:10.1016/S1090-5138(04)00005-4 URL [本文引用: 2]

Altruistic punishment in humans

DOI:10.1038/415137a URL [本文引用: 1]

A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation

DOI:10.1162/003355399556151 URL [本文引用: 1]

Parsing the behavioral and brain mechanisms of third-party punishment

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4499-15.2016

URL

PMID:27605616

[本文引用: 1]

The evolved capacity for third-party punishment is considered crucial to the emergence and maintenance of elaborate human social organization and is central to the modern provision of fairness and justice within society. Although it is well established that the mental state of the offender and the severity of the harm he caused are the two primary predictors of punishment decisions, the precise cognitive and brain mechanisms by which these distinct components are evaluated and integrated into a punishment decision are poorly understood. Using fMRI, here we implement a novel experimental design to functionally dissociate the mechanisms underlying evaluation, integration, and decision that were conflated in previous studies of third-party punishment. Behaviorally, the punishment decision is primarily defined by a superadditive interaction between harm and mental state, with subjects weighing the interaction factor more than the single factors of harm and mental state. On a neural level, evaluation of harms engaged brain areas associated with affective and somatosensory processing, whereas mental state evaluation primarily recruited circuitry involved in mentalization. Harm and mental state evaluations are integrated in medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate structures, with the amygdala acting as a pivotal hub of the interaction between harm and mental state. This integrated information is used by the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex at the time of the decision to assign an appropriate punishment through a distributed coding system. Together, these findings provide a blueprint of the brain mechanisms by which neutral third parties render punishment decisions.Punishment undergirds large-scale cooperation and helps dispense criminal justice. Yet it is currently unknown precisely how people assess the mental states of offenders, evaluate the harms they caused, and integrate those two components into a single punishment decision. Using a new design, we isolated these three processes, identifying the distinct brain systems and activities that enable each. Additional findings suggest that the amygdala plays a crucial role in mediating the interaction of mental state and harm information, whereas the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a crucial, final-stage role, both in integrating mental state and harm information and in selecting a suitable punishment amount. These findings deepen our understanding of how punishment decisions are made, which may someday help to improve them.Copyright © 2016 Ginther et al.

Action versus valence in decision making

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2014.01.003

URL

PMID:24581556

[本文引用: 1]

The selection of actions, and the vigor with which they are executed, are influenced by the affective valence of predicted outcomes. This interaction between action and valence significantly influences appropriate and inappropriate choices and is implicated in the expression of psychiatric and neurological abnormalities, including impulsivity and addiction. We review a series of recent human behavioral, neuroimaging, and pharmacological studies whose key design feature is an orthogonal manipulation of action and valence. These studies find that the interaction between the two is subject to the critical influence of dopamine. They also challenge existing views that neural representations in the striatum focus on valence, showing instead a dominance of the anticipation of action. Copyright © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Outcomes and intentions in children's, adolescents', and adults' second- and third-party punishment behavior

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2014.06.001

URL

PMID:24997554

[本文引用: 3]

Theories of morality maintain that punishment supports the emergence and maintenance of moral behavior. This study investigated developmental differences in the role of outcomes and the violator's intentions in second-party punishment (where punishers are victims of a violation) and third-party punishment (where punishers are unaffected observers of a violation). Four hundred and forty-three adults and 8-, 12-, and 15-year-olds made choices in mini-ultimatum games and newly-developed mini-third-party punishment games, which involved actual incentives rather than hypothetical decisions. Adults integrated outcomes and intentions in their second- and third-party punishment, whereas 8-year-olds consistently based their punishment on the outcome of the violation. Adolescents integrated outcomes and intentions in second- but not third-party punishment. Copyright © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

When punishment is emotion-driven: Children's, adolescents', and adults' costly punishment of unfair allocations

DOI:10.1111/sode.v29.1 URL [本文引用: 3]

Costly third-party interventions: The role of incidental anger and attention focus in punishment of the perpetrator and compensation of the victim

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.04.004 URL [本文引用: 1]

Effects of in-group favoritism and grade on the altruistic punishment behavior of primary school students

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.04.03 [本文引用: 1]

群体偏好与年级对小学生利他惩罚行为的影响

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.04.03 [本文引用: 1]

How infants and toddlers react to antisocial others

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1110306108

URL

PMID:22123953

[本文引用: 1]

Although adults generally prefer helpful behaviors and those who perform them, there are situations (in particular, when the target of an action is disliked) in which overt antisocial acts are seen as appropriate, and those who perform them are viewed positively. The current studies explore the developmental origins of this capacity for selective social evaluation. We find that although 5-mo-old infants uniformly prefer individuals who act positively toward others regardless of the status of the target, 8-mo-old infants selectively prefer characters who act positively toward prosocial individuals and characters who act negatively toward antisocial individuals. Additionally, young toddlers direct positive behaviors toward prosocial others and negative behaviors toward antisocial others. These findings constitute evidence that the nuanced social judgments and actions readily observable in human adults have their foundations in early developing cognitive mechanisms.

Face-to-face sharing with strangers and altruistic punishment of acquaintances for strangers: Young adolescents exhibit greater altruism than adults

Young adolescents are generally considered to be self-absorbed. Studies indicate that they lack relevant general cognitive abilities, such as impulse control, that mature in early adulthood. However, their idealism may cause them to be more intolerant of unfair treatment to others and thus result in their engaging in more altruistic behavior. The present study aimed to clarify whether young adolescents are more altruistic than adults and thus indicate whether altruistic competence is domain-specific. One hundred 22 young adolescents and adults participated in a face-to-face, two-round, third-party punishment experiment. In each interaction group, a participant served as an allocator who could share money units with a stranger; another participant who knew the allocator could punish the acquaintance for the stranger. Participants reported their emotions after the first round, and at the end of the experiment, the participants justified their behavior in each round. The results indicated that the young adolescents both shared more and punished more than did the adults. Sharing was associated with a reference to fairness in the justifications, but altruistic punishment was associated with subsequent positive emotion. In sum, greater altruism in young adolescents compared to adults with mature cognitive abilities provides evidence of domain-specificity of altruistic competence. Moreover, sharing and altruistic punishment are related to specific cognitive and emotional mechanisms, respectively.

Activity in the amygdala elicited by unfair divisions predicts social value orientation

DOI:10.1038/nn.2468

URL

PMID:20023652

[本文引用: 1]

'Social value orientation' characterizes individual differences in anchoring attitudes toward the division of resources. Here, by contrasting people with prosocial and individualistic orientations using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we demonstrate that degree of inequity aversion in prosocials is predictable from amygdala activity and unaffected by cognitive load. This result suggests that automatic emotional processing in the amygdala lies at the core of prosocial value orientation.

The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling

DOI:10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Marketing, consumer, and organizational behavior researchers interested in studying the mechanisms by which effects operate and the conditions that enhance or inhibit such effects often rely on statistical mediation and conditional process analysis (also known as the analysis of “moderated mediation”). Model estimation is typically undertaken with ordinary least squares regression-based path analysis, such as implemented in the popular PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS ( Hayes, 2013 ), or using a structural equation modeling program. In this paper we answer a few frequently-asked questions about the difference between PROCESS and structural equation modeling and show by way of example that, for observed variable models, the choice of which to use is inconsequential, as the results are largely identical. We end by discussing considerations to ponder when making the choice between PROCESS and structural equation modeling.

Fairness decision- making of college students in social dilemmas: Effect of social value orientation

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2012.05.004 [本文引用: 1]

大学生在社会困境中的公平决策: 社会价值取向的影响

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2012.05.004 [本文引用: 1]

The effect of oxytocin on third-party altruistic decisions in unfair situations: An fMRI study

DOI:10.1038/srep20236

URL

PMID:26832991

[本文引用: 1]

Humans display an intriguing propensity to help the victim of social norm violations or punish the violators which require theory-of-mind (ToM)/mentalizing abilities. The hypothalamic peptide oxytocin (OXT) has been implicated in modulating various pro-social behaviors/perception including trust, cooperation, and empathy. However, it is still elusive whether OXT also influences neural responses during third-party altruistic decisions, especially in ToM-related brain regions such as the temporoparietal junction (TPJ). To address this question, we conducted a pharmacological functional magnetic resonance imaging experiment with healthy male participants in a randomized, double-blind, crossover design. After the intranasal administration synthetic OXT (OXTIN) or placebo (PLC), participants could transfer money from their own endowment to either punish a norm violator or help the victim. In some trials, participants observed the decisions made by a computer. Behaviorally, participants under OXTIN showed a trend to accelerate altruistic decisions. At the neural level, we observed a strong three-way interaction between drug treatment (OXT/PLC), agency (self/computer), and decision (help/punish), such that OXTIN selectively enhanced activity in the left TPJ during observations of others being helped by the computer. Collectively, our findings indicate that OXT enhances prosocial-relevant perception by increasing ToM-related neural activations.

Helping or punishing strangers: Neural correlates of altruistic decisions as third-party and of its relation to empathic concern

DOI:10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00024

URL

PMID:25741254

[本文引用: 3]

Social norms are a cornerstone of human society. When social norms are violated (e.g., fairness) people can either help the victim or punish the violator in order to restore justice. Recent research has shown that empathic concern influences this decision to help or punish. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) we investigated the neural underpinnings of third-party help and punishment and the involvement of empathic concern. Participants saw a person violating a social norm, i.e., proposing unfair offers in a dictator game, at the expense of another person. The participants could then decide to either punish the violator or help the victim. Our results revealed that both third-party helping as well as third-party punishing activated the bilateral striatum, a region strongly related with reward processing, indicating that both altruistic decisions share a common neuronal basis. In addition, also different networks were involved in the two processes compared with control conditions; bilateral striatum and the right lateral prefrontal cortex (IPFC) during helping and bilateral striatum as well as left IPFC and ventral medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) during punishment. Further we found that individual differences in empathic concern influenced whether people prefer to help or to punish. People with high empathic concern helped more frequently, were faster in their decision and showed higher activation in frontoparietal regions during helping compared with punishing. Our findings provide insights into the neuronal basis of human altruistic behavior and social norm enforcement mechanism.

Third-party punishment as a costly signal of trustworthiness

DOI:10.1038/nature16981 URL [本文引用: 5]

The role of social value orientation in response to an unfair offer in the ultimatum game

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.07.006 URL [本文引用: 1]

Continuities and discontinuities in childhood and adult moral development

Children's judgments of interventions against norm violations: COVID-19 as a naturalistic case study

DOI:10.1016/j.jecp.2022.105452 URL [本文引用: 1]

Children's evaluations of third-party responses to unfairness: Children prefer helping over punishment

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104374 URL [本文引用: 2]

Punishing and compensating others at your own expense: The role of empathic concern on reactions to distributive injustice

DOI:10.1002/ejsp.v42.2 URL [本文引用: 3]

The development of social value orientation across different contexts

DOI:10.1080/00207594.2012.673725

URL

PMID:22551355

[本文引用: 3]

This study aimed to explore Chinese children's social value orientation across different ages and contexts. Revised decomposed games were used to measure the social value orientation of 9-, 11-, and 14-year-old children and college students as an adult group. About half of them were assigned to the hypothetical context of "equal payment group," providing equal compensation for participation in the study, and the others to the "real payment group," who got payment according to their own choices in the games. Results showed that 9- and 11-year-old children's choices differed between the two contexts: They made more prosocial choices in the hypothetical context, and more competitive choices in the "real payment" context. The 14-year-olds' and adults' choices were not significantly different in the two contexts. These results may imply that by 14 years of age, children have stable social value orientation, and their behavior reflects this value.

The development of children's fair behavior in different distribution situations

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.06.02 [本文引用: 4]

不同分配情境下儿童公平行为的发展

DOI:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.06.02 [本文引用: 4]

Research on the relationship between affective forecasting bias and decision making in adolescents

DOI:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2011.04.022 [本文引用: 1]

青少年情绪预测偏差与决策的关系研究

DOI:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2011.04.022 [本文引用: 1]

The developmental foundations of human fairness

DOI:10.1038/s41562-016-0042 URL [本文引用: 4]

Costly third-party punishment in young children

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.013

URL

PMID:25460374

[本文引用: 2]

Human adults engage in costly third-party punishment of unfair behavior, but the developmental origins of this behavior are unknown. Here we investigate costly third-party punishment in 5- and 6-year-old children. Participants were asked to accept (enact) or reject (punish) proposed allocations of resources between a pair of absent, anonymous children. In addition, we manipulated whether subjects had to pay a cost to punish proposed allocations. Experiment 1 showed that 6-year-olds (but not 5-year-olds) punished unfair proposals more than fair proposals. However, children punished less when doing so was personally costly. Thus, while sensitive to cost, they were willing to sacrifice resources to intervene against unfairness. Experiment 2 showed that 6-year-olds were less sensitive to unequal allocations when they resulted from selfishness than generosity. These findings show that costly third-party punishment of unfair behavior is present in young children, suggesting that from early in development children show a sophisticated capacity to promote fair behavior. Copyright © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Infants distinguish antisocial actions directed towards fair and unfair agents

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0110553 URL [本文引用: 1]

Relationship between peer acceptance and social strategies in 10-12 years old children

10-12岁儿童的同伴接纳类型与社交策略

Ultimatum bargaining by children and adults

DOI:10.1016/S0167-4870(98)00017-8 URL [本文引用: 1]

Measuring social value orientation

DOI:10.1017/S1930297500004204

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Narrow self-interest is often used as a simplifying assumption when studying people making decisions in social contexts. Nonetheless, people exhibit a wide range of different motivations when choosing unilaterally among interdependent outcomes. Measuring the magnitude of the concern people have for others, sometimes called Social Value Orientation (SVO), has been an interest of many social scientists for decades and several different measurement methods have been developed so far. Here we introduce a new measure of SVO that has several advantages over existent methods. A detailed description of the new measurement method is presented, along with norming data that provide evidence of its solid psychometric properties. We conclude with a brief discussion of the research streams that would benefit from a more sensitive and higher resolution measure of SVO, and extend an invitation to others to use this new measure which is freely available.

Five rules for the evolution of cooperation

DOI:10.1126/science.1133755

URL

PMID:17158317

[本文引用: 1]

Cooperation is needed for evolution to construct new levels of organization. Genomes, cells, multicellular organisms, social insects, and human society are all based on cooperation. Cooperation means that selfish replicators forgo some of their reproductive potential to help one another. But natural selection implies competition and therefore opposes cooperation unless a specific mechanism is at work. Here I discuss five mechanisms for the evolution of cooperation: kin selection, direct reciprocity, indirect reciprocity, network reciprocity, and group selection. For each mechanism, a simple rule is derived that specifies whether natural selection can lead to cooperation.

Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers

DOI:10.1006/obhd.1996.0100 URL [本文引用: 1]

The influences of social value orientation on prosocial behaviors: The evidences from behavioral and neuroimaging studies

DOI:10.1360/N972016-00631 [本文引用: 3]

社会价值取向对亲社会行为的影响:来自行为和神经影像学的证据

DOI:10.1360/N972016-00631 [本文引用: 3]

Third-party punishers are rewarded, but third-party helpers even more so

DOI:10.1111/evo.12637

URL

PMID:25756463

[本文引用: 1]

Punishers can benefit from a tough reputation, where future partners cooperate because they fear repercussions. Alternatively, punishers might receive help from bystanders if their act is perceived as just and other-regarding. Third-party punishment of selfish individuals arguably fits these conditions, but it is not known whether third-party punishers are rewarded for their investments. Here, we show that third-party punishers are indeed rewarded by uninvolved bystanders. Third parties were presented with the outcome of a dictator game in which the dictator was either selfish or fair and were allocated to one of three treatments in which they could choose to do nothing or (1) punish the dictator, (2) help the receiver, or (3) choose between punishment and helping, respectively. A fourth player (bystander) then sees the third-party's decision and could choose to reward the third party or not. Third parties that punished selfish dictators were more likely to be rewarded by bystanders than third parties that took no action in response to a selfish dictator. However, helpful third parties were rewarded even more than third-party punishers. These results suggest that punishment could in principle evolve via indirect reciprocity, but also provide insights into why individuals typically prefer to invest in positive actions. © 2015 The Author(s).

The transsituational influence of social norms

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.64.1.104 URL [本文引用: 1]

The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game

DOI:10.1126/science.1082976

URL

PMID:12805551

[本文引用: 2]

The nascent field of neuroeconomics seeks to ground economic decision making in the biological substrate of the brain. We used functional magnetic resonance imaging of Ultimatum Game players to investigate neural substrates of cognitive and emotional processes involved in economic decision-making. In this game, two players split a sum of money;one player proposes a division and the other can accept or reject this. We scanned players as they responded to fair and unfair proposals. Unfair offers elicited activity in brain areas related to both emotion (anterior insula) and cognition (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex). Further, significantly heightened activity in anterior insula for rejected unfair offers suggests an important role for emotions in decision-making.

Normative influence on altruism

In

Neurobiological mechanisms of responding to injustice

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1242-17.2018

URL

PMID:29459373

[本文引用: 2]

People are particularly sensitive to injustice. Accordingly, deeper knowledge regarding the processes that underlie the perception of injustice, and the subsequent decisions to either punish transgressors or compensate victims, is of important social value. By combining a novel decision-making paradigm with functional neuroimaging, we identified specific brain networks that are involved with both the perception of, and response to, social injustice, with reward-related regions preferentially involved in punishment compared with compensation. Developing a computational model of punishment allowed for disentangling the neural mechanisms and psychological motives underlying decisions of whether to punish and, subsequently, of how severely to punish. Results show that the neural mechanisms underlying punishment differ depending on whether one is directly affected by the injustice, or whether one is a third-party observer of a violation occurring to another. Specifically, the anterior insula was involved in decisions to punish following harm, whereas, in third-party scenarios, we found amygdala activity associated with punishment severity. Additionally, we used a pharmacological intervention using oxytocin, and found that oxytocin influenced participants' fairness expectations, and in particular enhanced the frequency of low punishments. Together, these results not only provide more insight into the fundamental brain mechanisms underlying punishment and compensation, but also illustrate the importance of taking an explorative, multimethod approach when unraveling the complex components of everyday decision-making. The perception of injustice is a fundamental precursor to many disagreements, from small struggles at the dinner table to wasteful conflict between cultures and countries. Despite its clear importance, relatively little is known about how the brain processes these violations. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, we combine methods from neuroscience, psychology, and economics to explore the neurobiological mechanisms involved in both the perception of injustice as well as the punishment and compensation decisions that follow. Using a novel behavioral paradigm, we identified specific brain networks, developed a computational model of punishment, and found that administrating the neuropeptide oxytocin increases the administration of low punishments of norm violations in particular. Results provide valuable insights into the fundamental neurobiological mechanisms underlying social injustice.Copyright © 2018 the authors 0270-6474/18/382944-11$15.00/0.

Three-year- old children intervene in third-party moral transgressions

DOI:10.1348/026151010X532888 URL [本文引用: 1]

An exploration of third parties' preference for compensation over punishment: Six experimental demonstrations

DOI:10.1007/s11238-018-9665-9 URL [本文引用: 1]

Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: Theory and preliminary evidence

The authors adopt an interdependence analysis of social value orientation, proposing that prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations are (a) partially rooted in different patterns of social interaction as experienced during the periods spanning early childhood to young adulthood and (b) further shaped by different patterns of social interaction as experienced during early adulthood, middle adulthood, and old age. Congruent with this analysis, results revealed that relative to individualists and competitors, prosocial individuals exhibited greater levels of secure attachment (Studies 1 and 2) and reported having more siblings, especially sisters (Study 3). Finally, the prevalence of prosocials increased--and the prevalence of individualists and competitors decreased--from early adulthood to middle adulthood and old age (Study 4).

Why we punish in the name of justice: Just desert versus value restoration and the role of social identity

DOI:10.1007/s11211-006-0028-2 URL [本文引用: 1]

The social value orientation of students in the period of compulsory education - A survey in Shanghai, Hangzhou and Hefei [Unpublished master’s thesis]

义务教育阶段学生的社会价值取向研究——基于上海、杭州、合肥三地的调查 (硕士学位论文)

Reward, punishment, and prosocial behavior: Recent developments and implications

DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.003 URL [本文引用: 1]

Neural mechanisms of the mood effects on third-party responses to injustice after unfair experiences

DOI:10.1002/hbm.v43.12 URL [本文引用: 2]

2-12 years old Chinese children’s emotional words usage of research [Unpublished master’s thesis]

2-12岁汉语儿童情绪词使用情况的研究 (硕士学位论文)

Theories and measurement methods of social value orientation related to decision making

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00048

[本文引用: 1]

<p>Standard economic models of decision-making draw on the self-interest hypothesis, which indicates that people are rational and motivated by personal benefit. However, in situations of interdependence, individual’s social motives are more complex and feature larger individual differences. Social Value Orientation (SVO), referring to a preference for particular patterns of outcomes for oneself in relation to others in interdependent situations, is a concept that characterizes individual differences in the level of concern an individual has for others. The current study reviews three types of existing measurement methods of SVO (Triple-Dominance Scale, Ring Measure, and Slider Measure), highlights their strengths and weaknesses, and briefly summarizes recent research on SVO in decision making, social cognition, empathy, and prosocial behavior. Future research on SVO needs to investigate the interactions of SVO and social factors, as well as the neural mechanisms associated with different SVOs.</p>

决策中社会价值取向的理论与测评方法

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00048

[本文引用: 1]

传统经济学决策理论强调利己性假设, 认为个体是理性的并由个人利益所驱动的。但是, 个体在相依情境中的社会动机要比利己性假设更为复杂, 具有较大的个体差异。社会价值取向是指个体在相依情境中对自己收益和他人收益分配的特定偏好, 是一个用来描述个体对他人利益关注程度的个体差异的概念。本文回顾了测量社会价值取向的三优势测量、环形测验和滑块测验等方法, 强调了不同测评方法的优点与不足, 并简要总结了决策、社会认知、共情、亲社会行为等领域内相关的社会价值取向研究。未来的研究则需要探索社会价值取向与不同社会因素的交互作用, 以及不同社会价值取向个体的神经机制等方面的研究。